Previously, I explored the

contentions surrounding the construction of the GERD and the reluctance of

Sudan and particularly Egypt, to welcome it due to risks of water shortages and

thus food production scarcities for the lower riparians. However, there may be

argument that the construction of the GERD may be synergetic in what it could

offer these three nations.

Escalating tensions between

Ethiopia and principally Egypt over the dam’s constructions is partially

unwarranted and based on misunderstandings on the risks associated with the

GERD for downstream waterflow. It is unrealistic to assume no risks will

present themselves with such a large structure, but it is not without its advantages.

A tripartite panel of experts

compiled of two representatives for each nation and four internationals,

investigated the construction of the GERD and any consequences it would have. The

final

report observed no dam[ning] adverse effects on Egypt and Sudan (see what I

did there!) There are benefits to the

GERD construction:

- - Reduced siltation in the Aswan High Dam(AHD)

- - Produces a more constant waterflow

- - Diminishes frequented flooding in Sudan

- - Reduced evaporation losses

- - Improved water management

WATER MANAGEMENT

A combination of agreed-upon basin-wide

cooperation can manage the risks associated with the dam (Wheeler et

al 2016). Annual releases of water from the GERD with drought control

at the AHD will diminish risks of desertifying arable land, regulate

agriculture through a robust plan in place to reduce waterflow uncertainty and

maintain a healthy water-level at the AHD for Egypt to continue to use (Mohamed 2017).

In fact, if the riparians are able to agree on terms of ownership rights of the

GERD, Egypt and Sudan could guarantee water release before the agricultural

season, decreasing Egypt’s water

loss by 6%.

EVAPORATION

Egypt receives an average of 12mm

of rainfall annually and heavily relies on irrigation to cultivate land for

food production (Abdel-Shafy

et al 2010). Only 6%

of the country is arable and agricultural land, leading to excessive

watering whereby gallons of water are dumped over the crops, resulting in

wasted water. As much as 6.3mm day−1 of water is evaporated from

Laker Nasser based on the yearly average of daily evaporation (Omran

& Negm 2018), roughly 12.million m3 annually (ibid), increasing

water use and stress to continue food production. Nevertheless, a report discovered

that the agreed-upon 6-year filling period of the GERD is adequate in

minimising impacts on current irrigated water demands and reduces evaporation

by 22%. Egypt can continue to utilise the AHD at a 96% reliability level,

positively affecting food production as there is less water wasted in the dry

region.

CLIMATE VARIABILITY

Egypt and Sudan are heavily

reliant on the upstream headwaters of the Ethiopian highlands for their water

supply, however with climate change, analysis indicates unprecedented levels of

interannual and interdecadal variability in rainfall and river flow(Conway

2005). The Ethiopian Highlands reveal a declining trend in its rainfall (Awange

et al 2014). The GERD will alter the economic advantages and

hydrological state of the riparians, saving more than US$680 million annually

from protecting water resources (Nigatu

& Dinar 2016). Thus, the regulation of the Nile waters, by extension

Nasser lake, reduces the impacts of climate variability on Egypt’s food

production by regulating flows, reducing evaporation, and allowing greater

freedoms in money available for investment into climate adaptations. In a

food-insecure environment like Egypt’s and looming climate change, freedom to

invest in adaptations for food production reduces the vulnerability of the

agricultural sector, increasing food security (Fahim

et al 2013). Increasing capacities of water management, constant

waterflow and reduced evaporation, means the GERD enables a more resilient

Nile. Thus, the riparians can focus on improving seawater desalinisation, maximising

efficiencies in water use, irrigation and improve rain harvesting techniques,

to combat escalating climate variability.

Agriculture constitutes 97% of

total water withdrawal in Sudan, especially considering it has the largest area

under cereal production in the Nile basin

(Ayana

& Srinivasan 2019). Therefore, understanding the changes to hydrology

to upstream Ethiopia due to the construction of the GERD better facilitates

Sudan to mitigate risk through the development of water budgets under various

management scenarios (ibid).

Egypt and Sudan need to acknowledge Ethiopia’s right to develop its water resource infrastructure and acknowledge the benefits of the GERD. However, the benefits I have outlined can only occur through tripartite cooperation.

So…

Will they adapt?

This is once again an insightful post with a great use of statistics, graphs and literature which clearly illustrates why water is so vital to the Nile. Could you give us an insight into what goods are produced here? Your use of subheadings works very well in this post so make sure its consistent throughout all of them. I feel your conclusion could be a lot more explicit, maybe by using subheadings it will be clear what your conclusion is. But in general, as always this is great!

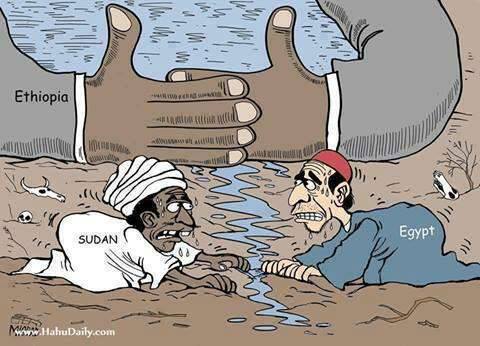

ReplyDeleteI, again, really enjoyed this post; the cartoon at the start is great! Perhaps you could summarise with a sentence at the start and end just to explain the overall point/goal of this post?

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed reading and interacting with the media you used in this post! The mixture of stats, visual map and the YouTube Video shows the breadth of material you have covered. Only criticism would be if you have a clearer concluding point, otherwise this was really good!

ReplyDelete